Overall market stability masks sharp divergence of returns within markets; Banking turmoil re-ignites fears of recession

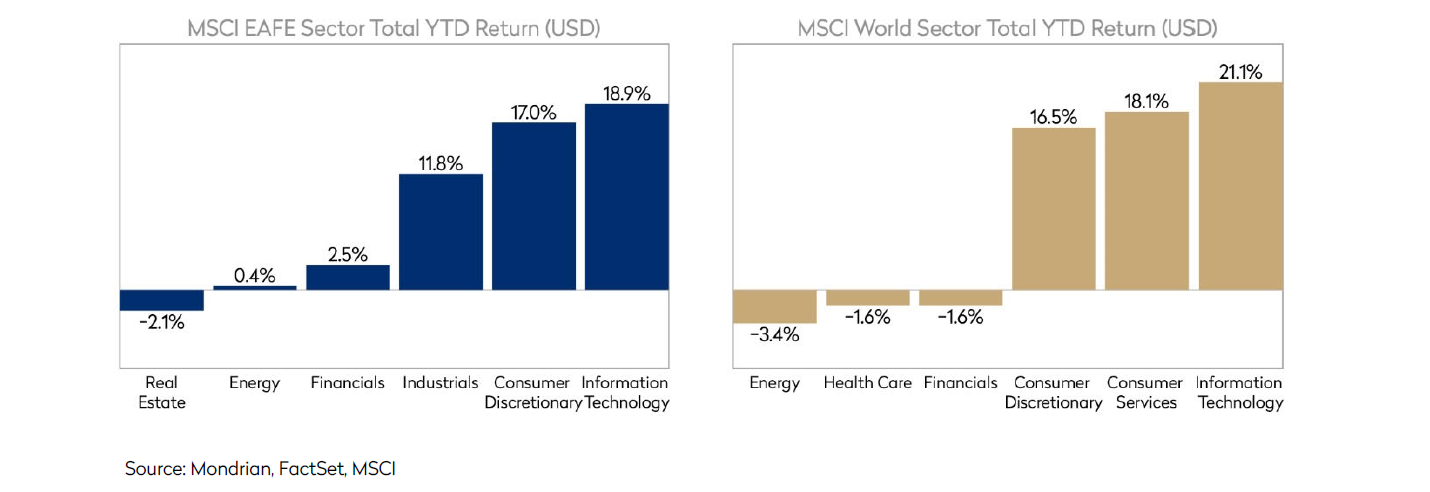

To date, it would be fair to say that the resilience of economies and of the broader financial system to the breakneck speed of monetary tightening has come as a positive surprise. While equity markets, especially in the frothiest end of the market, had a torrid year in 2022, for the most part, it did not seem to have affected ‘Main Street’: there were no clear signs of stress in the system and most of the attention seemingly focused on the dynamics around inflation, interest rates and economic growth. Alas, in recent weeks, fissures have appeared in the global banking system; the collapse of several regional banks in the US triggered global weakness in bank share prices with the resulting turmoil in financial markets ultimately leading to the rescue of Swiss banking giant Credit Suisse. While central banks continued to raise rates in the aftermath of the banking collapses, broader market interest rate expectations shifted lower as investors anticipated a slower pace of rates increases to ease pressure in financial markets. Expectations for lower rates, coupled with recessionary fears and a rush for financial safety led to a volatile quarter for global markets. There was significant divergence between sector returns with growth-oriented sectors notably outperforming the value-oriented and the more traditionally defensive sectors.

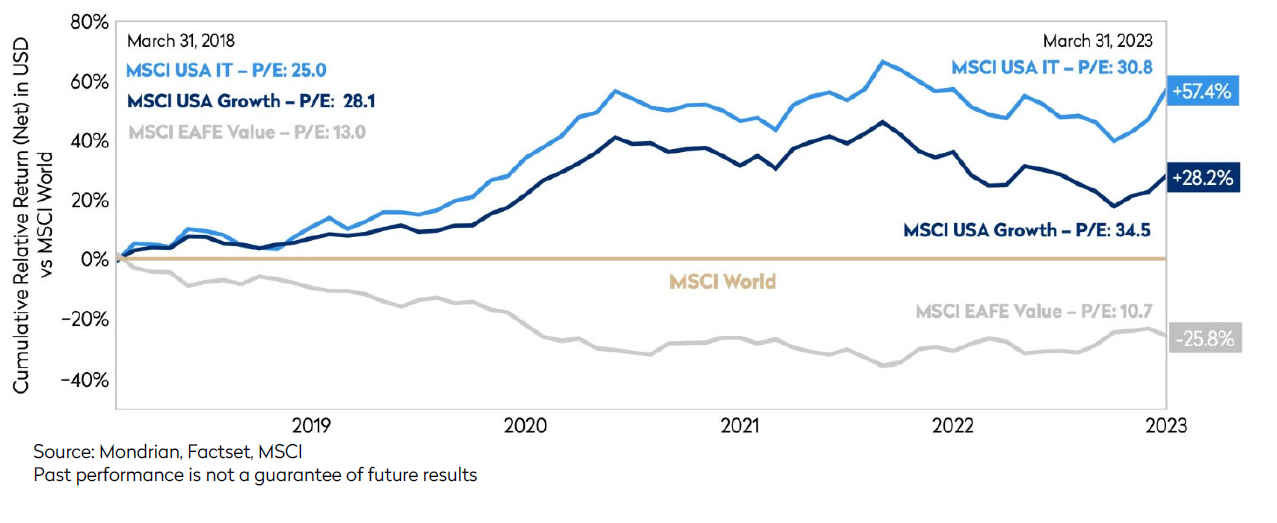

The MSCI World growth sub-index outperformed the value sub-index by an astounding 1400 basis points in the first quarter of this year. As one of the widest quarterly divergences in returns since the inception of the MSCI style sub-indices in 1975, this was even more notable as it was primarily driven by a sharp bifurcation of value and growth returns in just one market, albeit a large one, the US.

While we can justifiably understand the concerns around the banking sector and the earnings impact on more cyclical sectors of the market, we do not believe, for example, that industries such as semiconductors should be immune to any economic weakness. Moreover, the valuation of the US growth sub-sector has increased despite interest rates staying high relative to their average in the last decade as well as growing recessionary risks.

US Regional Banking stress triggered by the rise in interest rates and the sharp inversion of the yield curve which led to bond losses and deposit flight

Stress in the global banking system in the first quarter can be traced back to the wind down of Silvergate Bank in California in March. This was a bank that focused on providing services to digital asset firms. It was hit by a flood of deposit outflows in the fourth quarter of 2022, catalyzed by the collapse of the digital asset exchange FTX. To meet deposit outflows, the bank was forced to sell debt securities at a loss. This highlighted the risk to capital from its securities portfolio and ultimately led to the decision to liquidate the bank. Similar concerns about embedded losses in long term bond holdings led to rapid (ironically technology-enabled) deposit flight and the subsequent failures of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank.

Issues at SVB had been brewing for a while. As self-proclaimed bankers to the “innovation economy”, they had outsized exposure to venture-capital (VC) funds and those funds’ portfolio companies. In the tech-boom that followed covid, the bank experienced a huge inflow of deposits, a reflection of the surge in VC deal activity at the time. As this tech-boom reversed in 2022, so did the deposit inflows. The bank had invested these deposits in a large portfolio of liquid securities that could in theory be sold to fund the deposit outflows, but as with Silvergate, the rise in interest rates meant these could only be sold at a loss. Initially, the bank turned to expensive wholesale funding, resulting in a negative impact on earnings. As a result of these dynamics, the bank’s share price fell significantly in 2022. With unfortunate timing and possibly some naivete, management announced they had sold debt securities at a loss and would look to shore up the bank’s capital base through an equity raising on the day that Silvergate announced they would liquidate. Compounding their problem, the capital raise was neither large enough to reassure the market nor fully underwritten. It instead sparked panic in depositors and investors: SVB’s share price dropped 60% on the day and, with a few clicks of a mouse, $42bn of deposits left the bank. SVB was closed the following day.

The collapse of SVB triggered a wider reassessment of banks with a focus on two areas in particular: the nature of the deposit base and unrealized losses on securities portfolios. SVB had a highly concentrated deposit base, but also, crucially, one where 88% were uninsured. Signature Bank had some similarities with Silvergate and SVB in terms of its exposure to digital asset and VC companies and was caught up in the bankruptcy of FTX. But it also resembled SVB with regard to nervous uninsured deposits, with 90% of deposits over the $250k FDIC insured limit. The bank lost 20% of its deposits in hours after the announcement of SVB’s failure. Deposit outflows escalated over the weekend and the bank was shut down on the Sunday.

Despite the FDIC extending deposit protection to all the depositors of SVB and Signature Bank, other US banks have seen their liquidity tested in subsequent weeks. Depositors have fled to the safety of the largest banks and the higher yields offered by money market funds. Data from the Federal Reserve shows system-wide deposit outflows of $262bn in the two weeks since the Silvergate liquidation, with the majority coming from smaller banks. Borrowing from the Federal Reserve’s discount window and newly created Bank Term Funding Program stood at $153bn at the end of March and Federal Home Loan Bank outstanding debt increased by $247bn in the same month, reflecting increased demands for funding by banks. These are significant numbers and there will be individual banks struggling to cope but, at this stage, in the context of total US bank deposits of $17.4 trillion, they do not suggest a systemic issue in the banking system.

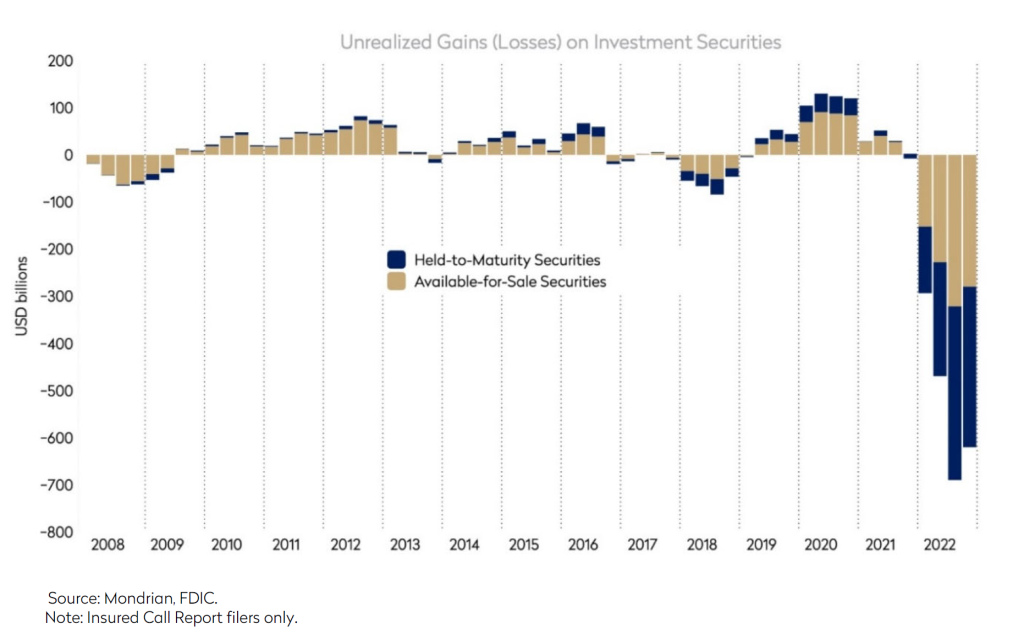

There are though, several areas that we continue to watch. Although it was runs on their deposits that ultimately caused the failure of these banks, it was the losses on their securities portfolios that triggered them and limited their ability to meet the liquidity demands. The fact that these losses are not recognised in regulatory capital, unlike larger US peers and banks globally, had made management and investors complacent. This is a vulnerability for the wider US banking system and stems from the massive influx of deposits during covid thanks to a rapid expansion in quantitative easing, government stimulus and lock-down savings. With more limited opportunities for lending, commercial banks saw deposit growth outpace loan growth by $4.0 trillion between the end of 2019 and the end of 2021. The result was a significant expansion in the securities portfolios of banks. With interest rates at record low levels, this investment in bonds by banks couldn’t have happened at a worse time. As interest rates rose rapidly through 2022, losses on these bonds ballooned to over $600bn. At the same time, with covid savings now being spent, depositors switching to more lucrative money market funds and the Federal Reserve engaging in quantitative tightening (QT), US commercial bank deposits are declining at a record pace and securities portfolios can’t be used to meet these withdrawals without crystallizing losses.

Contagion claimed Credit Suisse, but wider contagion outside the US looks unlikely

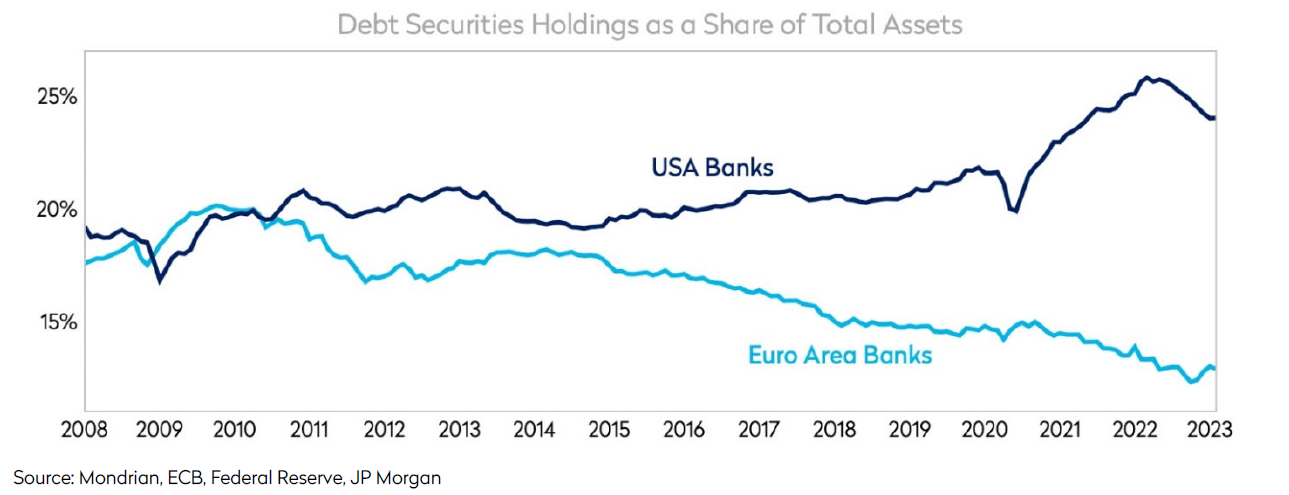

The demise of Credit Suisse in the week following the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank triggered serious concerns of a systemic global banking crisis. While recognizing the seriousness of the events, there are reasons to believe that the situation is unlikely to cascade or lead to a systemic global banking crisis. Most evidently, the banks that have failed in the US had unique business models. Unlike US banks, European banks’ debt holdings are typically ~10% of total assets, with a lower average duration reducing interest rate risk. Post-GFC accounting rules have generally required European banks to recognize most losses on their bond portfolios in regulatory capital and, while rising, yield curves are still typically less inverted across other developed markets.

Banks in Europe typically have a highly diverse customer base with customers covering all segments of the economy. This stems from the more concentrated nature of banking in Europe with less room and lower potential systemic impact for banks with niche business models. More generally, European banks are also very liquid: loan-to-deposit ratios are typically ~1.0x and liquidity coverage ratios (LCR) are mostly >150% against ~115-120% at the largest US banks.¹ Moreover, while there is some anecdotal evidence that European based depositors are now focusing on money market funds and other investments to increase interest income, the risk that increased scrutiny on unrealized bond losses could trigger deposit outflows seems remote, at least at a system level. This is to say, European banks face plenty of risks, but events in the US have not exposed some sort of systemic issue on this side of the Atlantic.

Nevertheless, Credit Suisse did succumb to escalating capital and liquidity concerns about a week after SVB’s collapse. As many will know, Credit Suisse has been struggling for many years. Over the last 10 years, the bank made a cumulative loss of c.$4 billion and has appeared to stumble from one crisis to the next: the entanglement with Greensill, the $5.5 billion hit from Archegos Capital Management (Bill Hwang’s family office), and the Mozambique “tuna bonds” loan scandal are just a few colorful examples (among others!) from the very recent past. Ultimately, the leverage that is inherent in fractional reserve banking means that no-one can survive a run on deposits.² Credit Suisse’s reputation was so tarnished from its losses, the rolling restructurings, the scandals, and the management upheavals, that finally depositors took flight and the Swiss authorities could not break the reflexive feedback loop between the perception of the bank and its ability to keep functioning.

Financial stability has returned; while not GFC 2, significant longer-term uncertainty remains

Looking back to the Global Financial Crisis, the underlying dynamics are different today. Back in 2007-08, thinly-capitalized banks were taking (with hindsight) excessive credit risks. This time, banks appear to have ample capital and credit risk has not (so far, at least) been a factor. Rather, certain banks were caught out by the sudden sharp rise in short-term rates, a problem which was exacerbated by the surge in deposits during COVID and arguably, a ‘naïve’ ignorance of the riskiness of their deposit base and the duration risk embedded in their investment books.

Nevertheless, with banks observing a stressed market and now facing an incrementally more uncertain macroeconomic environment, the episode is likely to ensure that management teams and investors are laser-focused on measures of profitability and balance sheet resilience and this in turn is liable to squeeze the flow of credit to economies. The starting point in terms of capital and liquidity is strong so we would not expect to see a sharp adjustment in terms of bank behavior in a base case, but it is bound to have a cooling effect on the economy.³ If lending conditions look set to tighten, companies with high leverage and large refinancing requirements are likely to be under pressure.

Banks will face some incremental headwinds too, even in a relatively benign economic scenario. Banks in most countries have been very slow to pass interest rate hikes on to depositors, allowing the benefit from rising rates to feed into their net interest margins. But deposit re-pricing is already underway and bound to accelerate in the current environment. For many banks, deposit pricing and a mix shift from sight deposits to time deposits may soon become a bigger driver of net interest margins than asset yield expansion. What was a tailwind in the past 18 months for banks is turning into a headwind moving forward as deposit costs rise for banks. Combined with inflation, and potential asset quality issues, bank returns could easily come under pressure again.

Markets offer a wide range of outcomes: brace for volatility and expect the unexpected

Despite the initial wobble in equity markets and in particular, in banks, financials ended the quarter broadly flat while significantly lagging technology and their other more growth-oriented counterparts. This reaction broadly substantiates our initial view that the banking sector stress does not, at least yet, look likely to cascade into a GFC-style event. The failed US banks had unique business models and a severe and abrupt withdrawal of deposits coupled with unrealized losses on securities portfolios led to their demise. Nevertheless, the broader economy is likely to suffer from tighter credit conditions moving forward as banks see pressure on earnings from rising deposit costs and potentially rising non-performing losses and tighter regulation. The collapse of SVB and the issues in the US regional banking sector is a salutary reminder that, in the context of a record pace of monetary tightening, investors should brace for volatility and expect the unexpected.

Significant tensions remain in the system between inflation, interest rates, and financial stability. How they will resolve themselves is unknown. While stability has returned, it is worth remembering that banking crises can take time to emerge. It was over twelve months between the collapse of Northern Rock in the UK in 2007 and the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008. Mondrian invests our clients’ portfolios based on our assessment that the market is mis-valuing a company’s ability to generate free cash flow using a structured scenario analysis framework. Our objective is to maximize risk-adjusted returns for our clients, and we believe that this framework should prove to be particularly helpful in the current environment when economic uncertainty is significant and policy risks are high, with substantial divergence in opportunities in markets.

¹ The liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) is the ratio of high-quality liquid assets (HQLA) over the net liquidity outflows arising during a 30-day stress period. Banks are meant to operate in normal times with an LCR ≥ 100%.

² Even in its dying throes, Credit Suisse had healthy-looking capital and liquidity ratios (14.1% CET1 and 144% LCR at year-end).

³ Some investment banks have attempted to quantify this effect and estimates seem to be in the order of 50bps off economic growth.

Disclosures

Views expressed were current as of the date indicated, are subject to change, and may not reflect current views. All information is subject to change without notice. Views should not be considered a recommendation to buy, hold or sell any investment and should not be relied on as research or advice.

This document may include forward-looking statements. All statements other than statements of historical facts are forward-looking statements (including words such as “believe,” “estimate,” “anticipate,” “may,” “will,” “should,” “expect”). Although we believe that the expectations reflected in such forward-looking statements are reasonable, we can give no assurance that such expectations will prove to be correct. Various factors could cause actual results to differ materially from those reflected in such forward-looking statements.

This material is for informational purposes only and is not an offer or solicitation with respect to any securities. Any offer of securities can only be made by written offering materials, which are available solely upon request, on an exclusively private basis and only to qualified financially sophisticated investors. The information was obtained from sources we believe to be reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed and it may be incomplete or condensed. It should not be assumed that investments made in the future will be profitable or will equal the performance of any security referenced in this paper. Past performance is not a guarantee of future results. An investment involves the risk of loss. The investment return and value of investments will fluctuate.

Past performance is not a guarantee of future results

This marketing communication is for Professional Investors only.